A medieval Hebrew author would certainly have known both Hebrew vocabulary and grammar better than Hannig wants us to believe.I refer to the words ‘ginnaḥ’ (“groaned”), ‘ šlh’ (“to be quiet, at ease”), ‘shorba’ (“soup”, in Arabic, not Hebrew), ‘mtim’ (“people”), ‘*jil = jelel’ (“wailing”), ‘haalayah’ (“raising, lifting”), ‘ha-qam’ (“enemy”), ‘*w-ˁiot’ (“ruins”), and so many more.The words Hannig extracted are often incredibly archaic forms, rarely, if ever, found in medieval Hebrew texts.

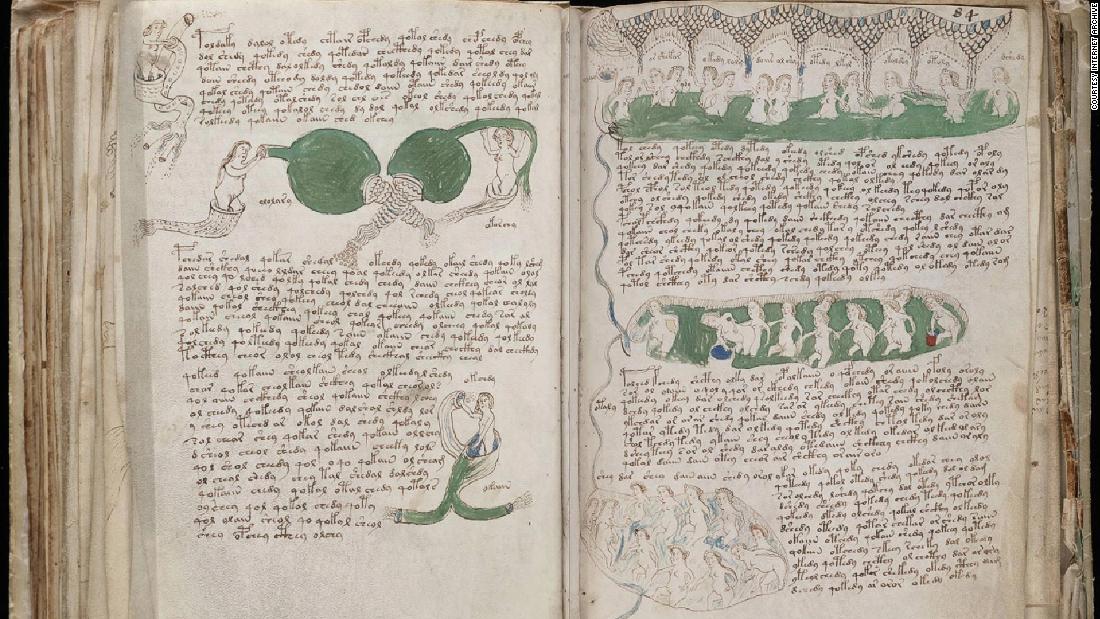

As a reader of Hebrew, I struggled to understand how he interpreted the symbols, each time anew. Hannig interprets these vowels inconsistently and at times arbitrarily. Hebrew does not have vowels in the Indo-European sense of the word, so it is curious that someone would introduce these characters, making the target word practically unrecognizable. Hannig’s mapping includes symbols representing “vowels” (i.e., a symbol looking like a lowercase ‘a’, and another resembling a lowercase ‘o’).I can accept that two forms of the S sound (i.e., the letters SAMECH and SIN) are represented by one symbol, but M and N is difficult to accept. Some symbols are mapped to one of two very common Hebrew letters (e.g., the same symbol represents both M and N regular and final forms).At times, a Hebrew letter not in the Voynich is added, ostensibly to turn the transliterated characters into a word (e.g., ‘*jil = jelel’ (“wailing”), and extra ‘j’ was added).Occasionally, symbols found in the Voynich text are ignored and not transcribed to Hebrew (e.g., Teˁlᶟ תעה tˁh „irrte“, the “el” sound is ignored).The conversion of Voynich symbols to Hebrew letters is inconsistent:.In the end, I am entirely unconvinced with the method Hannig uses or with his decipherments. I worked as “close to the metal” as possible. I first wanted to see if I could duplicate what Hannig says he sees there, assessing the Hebrew / Aramaic he claims to read based on my knowledge of medieval Jewish liturgical and rabbinic texts.įollowing that, I wanted to pick a Voynich text of my choosing, and see if I could duplicate Hannig’s results. I was most interested in section D (“Vollstandige Texte und Textausschnitte” / “Full texts and excerpts”). Without passing any judgment on the proposed solution, I am reminded of David Kahn’s description of Elizabeth Gallup’s “decipherment” of Shakespeare’s works. I have printed out the paper in German and Google-translated to English (I am fluent in Yiddish / Judeo-German, so I don’t see a problem getting through Hannig’s paper). Having said that, each solution should be appraised based on its ability to decipher the manuscript, nothing else.

I agree with Klaus that one needs to “ramp up” for each new proposed solution, as there have been so many of them. Here’s what Moshe wrote me about Hannig’s proposed Voynich solution:

He is amazed and grateful for the wonderful publications, websites, conferences, and people giving of their time and energy to further classical cryptanalytic research, and looks forward to contributing to this extraordinary effort. Moshe told me that he has more research projects on the “back burner” than he can handle – a problem I know very well. I first heard about Moshe when I wrote my book Codeknacker gegen Codemacher, which covers the Chaocipher in the “Leichen im Krypto-Keller” (“Skeletons in the crypto Cupboard”) chapter. A reader of Cryptologia since 1977, he tracked down and published the first description of the Chaocipher algorithm, a cipher method that had been secret for decades. His interest in classical cryptanalysis began at age 15 after reading David Kahn’s classic The Codebreakers from cover to cover multiple times.

.jpg)

#Voynich manuscript solved software

Moshe is a software engineer residing in Jerusalem, Israel.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)